Italian documentary filmmaker Stefano P Testa has screened work in international film festivals His film ‘De Occulta Imagine’ premiered at Sheffield Docfest, going on to show in numerous festivals cross the globe. The film screened in ‘Treasure’ at Fabrica (October 2024)

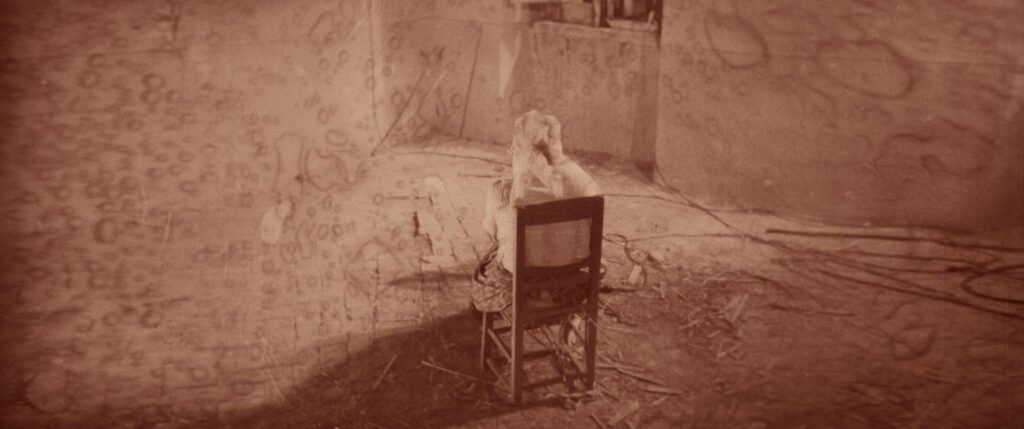

‘De Occulta Imagine’ -Every image has original meaning. And every image has potentially infinite meanings when re-placed and re-used in different contexts. Taking us on a deep dive into the Audio-visual Archive of the Labour and Democratic Movement in Italy, the director transforms images related to the ‘Southern Question’ – news reports and films from the 1960s that deal with the subordinate state of Southern Italy comparative to the North. Starting from these images of inequality, poverty, emigration, spirituality and superstition, De Occulta Imagine leans into the processes of alchemy.

Q. We saw the ‘treasure’ in your film as the huge value in preserving and reflecting on archive footage. Is this how you personally interpreted the theme?

ST: I certainly consider archival footage as a treasure to be preserved. In ‘De Occulta Imagine’ the ‘treasure’ is the multiplicity of latent meanings hidden behind every image. Metaphorically speaking: the meaning is buried somewhere on the island, but the map that leads to it is incomplete. You dig and you don’t know what you might find. Maybe a golden trunk, maybe just old bones.

Q. What drew you to working with archival footage and the residency in the Audiovisual Archive of the Labor and Democratic Movement. How different has the process been to your previous documentaries?

ST: I was aware of the preciousness and vastness of the AAMOD Archive, and I had long been waiting for the right opportunity to make use of it. The residency was the perfect opportunity. I applied together with Luca Severino – the music composer – and we were selected. Compared to my previous found footage films, ‘De Occulta Imagine’ is made up of archival footage. In ‘Moloch’ (2017, 82’) I found in a rubbish dump some boxes full of videotapes. In the ‘The Second Principle of Hans Liebschner’ (2020, 88’) I bought some anonymous family films at a flea market; the same occurred with ‘Dear Monster’ (2023, 16’). In these cases I had a limited amount of footage at my disposal, and I build the films based on that; in ‘De Occulta Imagine’ the process was reversed: starting from an idea, I searched within the huge archive for the material that best suited to represent it.

Q. The film’s cinematic alchemy, as it has been described, is a potent meld. Can you talk more about this term and how it fits with your filmic choices?

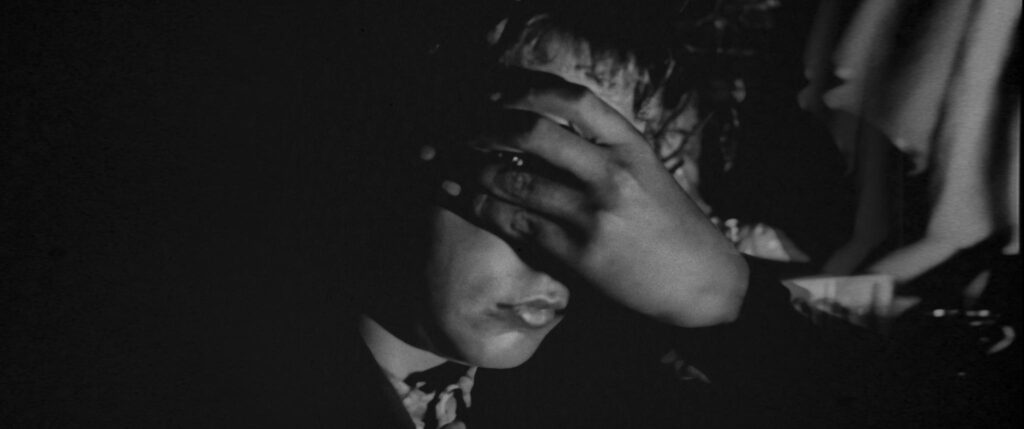

ST: It’s hard to explain in a few lines but I’ll try. I was inspired by some ancient alchemical texts, particularly concerning the processes of transforming matter: the transmutation of raw metals into pure gold. Alchemy books are extremely complex and ambiguous. The transmutation of matter is a process that is part of the Alchemist’s Work: the Magnum Opus. However, it should not be interpreted literally – it is not about physically turning lead into gold through mercury – but rather it describes the process of transitioning from one state to another. This can be a state of consciousness, a spiritual or psychophysical state. In my case, the ‘raw metals’ are the archival footage, while the ‘gold’ is the latent meaning contained within them. Furthermore, there’s a second reading level inspired by C. G. Jung’s psychoanalytic interpretation of alchemical processes. Dreams – representations of the deep – contain obscure symbols and elusive meanings. Even the alchemists worked with them. Hence, the attempt to give the film a dreamlike structure.

You describe the film as an ‘invitation to a semantic and emotional drift’ a fascinating phrase can you explain what that means to you?

ST: The film aims to invite the viewer to abandon logical and rational interpretative frameworks and instead surrender to emotional associations related to their own experience. Upon waking from a dream, one is confused and tries to make sense of it, but while the sensory stimuli may appear indecipherable or disjointed, the lingering emotional state that characterized the dream remains strong. I would like something similar to happen at the end of the film, so that the viewer might say to themselves: ‘I don’t know what I saw, but I feel…’

Q. How did the structure of the film evolve with the idea of the ‘southern question’ as you started delving into the archive?

Very interesting question, thank you. As the question itself suggests, the theme of the Southern Question emerged by chance and at a later stage in the film’s conception. While watching the films in the archive, I noticed that many documentaries dealing with this theme were made by strongly symbolic images. Women dressed in black, religious ceremonies, mining work, mothers and daughters, and so on. Exactly the kind of images I was looking for. The use of these clips in ‘De Occulta Imagine’ does not refer to an intentional political meaning. If anyone should find a political thread then it means that the residual meanings of those films are still alive.

Q. The film’s soundtrack is very compelling. Particularly powerful for screening in Fabrica, a former church. How did you approach your collaboration with Luca Severino on the music and sound design?

ST: Thank you so much, I would have loved to attend the screening. I’ve known Luca since we were children;. I often collaborate with him, and I know and respect his working method. During the making of the film, I would provide Luca with the images, stimuli, and concepts to work on, and then I would let him develop them on his own. Like me, Luca is also a person obsessed with his work, in an alchemical sense. We have no peace until we reach something that satisfies us. The problem is we are never satisfied. So at a certain point, before the obsession becomes dangerously pathological, we are forced to stop, postponing the much-desired and elusive sense of fulfillment to the next work, which is nothing else than the continuation of the Opus.

Q. What does future filmmaking look like for you? Will it see the inclusion of archive imagery?

ST: Yes, I think so. I really enjoy watching and reusing footage created by other people, in different times and places, far away from my comfort zone. I promise myself never to use archival footage or found footage in the same way: each film must be a different ‘device’ than the previous one. Better don’t take the joke too far.